IoT Boards I've Used

I really like the idea of IoT. Not so much vendors coming out with their own proprietary stacks and protocols, but rather ability to cheaply and easily gather and expose myself and my environment to the internet, and remotely adjust that environment. To that end, I've played around with a couple of different IoT boards, and am planning to keep a running list of my experiences here, mostly so I can remind myself of how to select amongst and use these boards in the future. With that said, let's jump right into this.

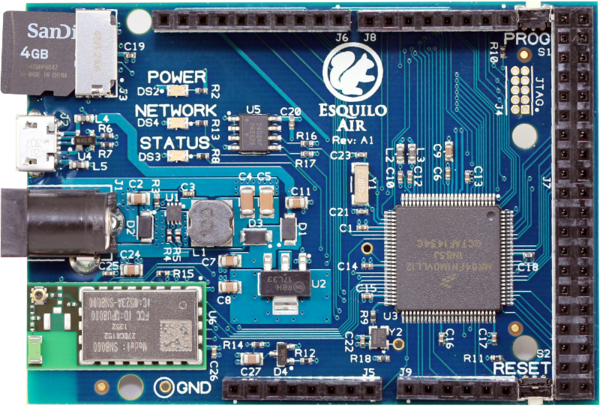

Esquilo

The esquilo is a wifi-enabled microcontroller with onboard filestorage, a webserver, a real-time operating system, and a bunch of GPIO pins and libraries to support them. The really cool, differentiating feature here is the onboard storage and webserver. Since the board runs its own webserver, the web-based IDE is served by the board itself. Once connected to your wifi, you can access the board from anywhere else on that network to program, debug, upload files or download files.

This is really cool, but it does have some disadvantages. First off, since the microcontroller is (I think) single-threaded, if your real-time program doesn't pause for enough time, the IDE will stop working. If you set the program to auto-boot, this means you won't be able to stop the program, or access the board through your browser. They've recently added a feature to turn off auto-boot via the reset button, so this issue is less pressing. It does mean that any programs you write need fairly significant pauses, however (around 100ms). This caused problems for our first esquilo project; for a house party, we intended to set up beat-controlled LED lighting. We were attemplting to do live beat detection on the esquilo, so that the DJ could easily tweak the constants or manually trigger beats, and so other networked devices could be triggered on beats. However, the long pauses put a very low cap on our sample rate, which in turn reduced the frequencies on which we could detect beats, and the complexity of our detection algorithm.

Another, more minor disadvantage is that the web UI is a bit clunky for uploading or downloading files. Normally this wouldn't be an issue, but for one project we experienced repeated SD card failures, and would need to re-upload all out libraries and code fairly frequently. On the other hand, the wifi network was flaky, so the ability to store data onboard and only transmit when possible was enormously useful.

The Squirrel language is nice, but uncommon. The documentation is nice, but examples are rare. However, the approach used to connect the webserver to the real-time OS is very elegant; a function is provided by a built-in javascript library which allows the browser to call functions on the RTOS, and receive the output. Getters and setters are straightforward, as are simple control interfaces.

I've got to say, I really like the esquilo. While a bit pricey (at USD$50), the device can support a lot of inputs and outputs, and makes it so fast and easy to develop and prototype local online interfaces, that I would use this device any time I'm trying to create a local hub for home automation, or any project where development speed is more important than public accessibility.

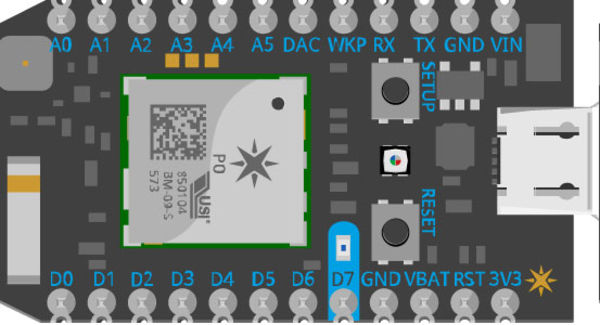

Particle Photon

Particle (formerly Spark) was an early Kickstarter success, providing an arduino-like board with easy connectivity to the public internet. They provide this connectivity by maintining servers to which your photon connects. This means you can monitor and reprogram your photon from anywhere on the internet, as well as send commands to the device. The former ability has come in useful several times, as we are using our photon to control the temperature of a beer-brewing refrigerator, and need to adjust the target temperature during the process. Getting data from the device is even easier; a simple curl command, piped into some file, is all it takes to log every event published by the device. My two complaints are the documentation can sometimes be organized in an unusual fashion, and the web-based IDE can be difficult to navigate. In particular, I wasn't able to keep both my own code and the code of one of the libraries I was using open simultaneously, making debugging a tedious process.

This is the board I've used the least, so I have the least to say about it. That being said, I really like the ease of pulling data from it. At USD$20 it's not that pricey. Also, while I haven't used it, the cellular capabilities of the electron model are pretty exciting. Based on my experience, I would recommend the Photon for situations with a moderate number of sensors and outputs, where connections from the public internet are an absolute must.

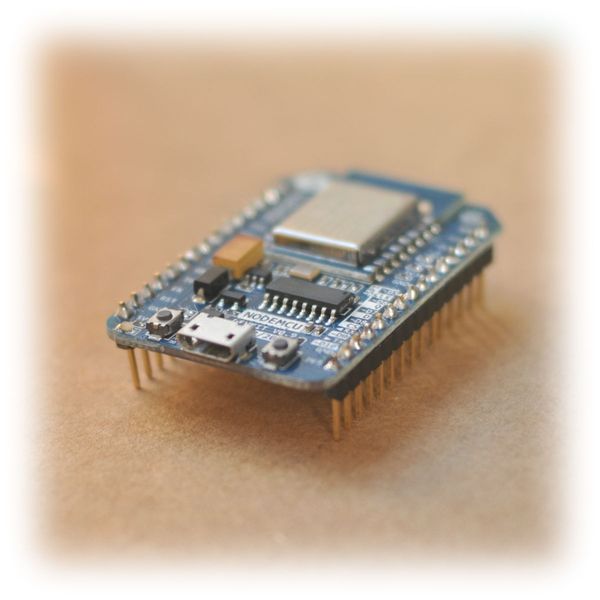

NodeMCU

A few years back, the easiest way to create IoT boards was to stick a wifi shield on an arduino. Turns out, the chip running the wifi board is a pretty powerful microcontroller in its own right. Some clever hardware hackers decided to ditch the Arduino, and simply provide GPIO pins on the wifi chip itself, specifically the ESP8266. This means the devices are cheap--you can find them on Ali Express for less than $5 apiece.

NodeMCU is a breakout board for the ESP8266, and firmware for that layout. The firmware is based on Lua, which is a nice choice, as it has a lot of documentation and a straightforward syntax. Installing libraries is a bit... different, as you need to compile the firmware with the libraries you need, then flash that firmware to the node. However, there are two great tools that make that pretty much painless: NodeMCU-build and the nodemcu-flasher tool. NodeMCU-build is a website which lets you check off the libraries you want (complete with links to excellent documentation on each), and will email you the compiled firmware. The nodemcu-flasher tool is a piece of windows software which make it easy to flash that firmware to the nodeMCU. Once flashed, the ESPlorer tool can be used to connect to the node, enter a lua repl, or upload your own code. If you have a file titled lua.init, the node will execute that code on startup.

I was really pleased with the ease design of the wireless libraries. It took some debugging for wireless, as my network was spotty, but it is trivial to send POST or GET requests to a server, once the node is up and running. Those functions failed in sensible ways, dropping the attempt if the network was unreachable. My greatest problem with the nodeMCU was its serial timeout. In order to avoid a problem analogous to the IDE starvation in the esquilo, the NodeMCU will crash and restart if it is unresponsive over serial for a long enough time. The problem is, error message upon that crash is incredibly difficult to understand. This also means your code can't depend on any long-running loops. Instead, it should use callbacks, timers, and short, simple functions.

Given the low price, callback-oriented nature, and ease of hitting outside servers, I recommend the NodeMCU for situations where you are performing simple I/O operations, in particular gathering data from popular sensor models, and want a lot of boards-say one board per sensor.